Unlocking the Tumour Microenvironment: Advances in Single-Cell and Spatial Analysis

An Oxford Global Thought Leadership Session

The tumour microenvironment (TME) has become one of the most influential concepts in modern cancer research. No longer viewed as a passive backdrop to malignant growth, the TME is now recognised as a dynamic, highly organised ecosystem that actively shapes tumour evolution, immune response, therapeutic resistance, and ultimately patient outcomes. Recent advances in single-cell and spatial analysis have played a pivotal role in driving this shift, offering unprecedented resolution into the cellular and molecular architecture of cancer.

To explore how these technologies are reshaping research and clinical translation, Oxford Global convened a one-hour virtual thought leadership session bringing together experts across academia, clinical oncology, pathology, genomics, and computational science. The session featured a keynote interview with Professor Evan Keller, followed by a panel discussion with Professor Simpa Salami, Dr. Carlo Bifulco, Professor Veera Baladandayuthapani, and Dr. Egon Ranghini.

From background context to biological driver

Opening the session, Professor Keller, Professor of Urology and Pathology at the University of Michigan, reflected on how his work in prostate cancer bone metastasis led him to focus on the tumour microenvironment. Prostate cancer’s strong predilection for bone highlighted that the surrounding tissue was not incidental but actively supportive of tumour growth. For many years, however, the tools available could not adequately dissect the complex interplay between tumour cells and the diverse cell populations within bone.

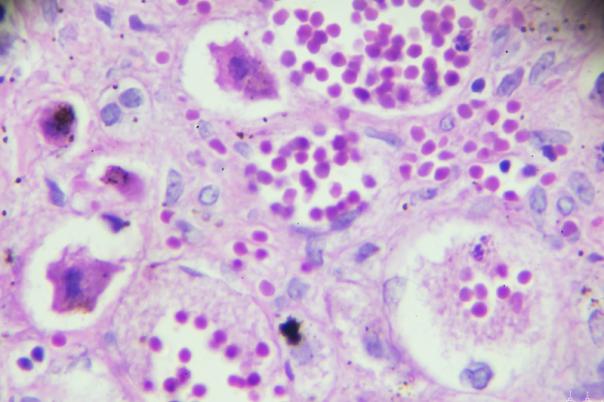

The emergence of single-cell technologies transformed this landscape. By enabling the profiling of individual cells rather than averaged tissue signals, these approaches allowed Professor Keller’s group to identify distinct cellular contributors to metastatic progression. Spatial technologies further expanded this insight by preserving tissue architecture, revealing how tumour cells, immune cells, and stromal components interact in situ. Together, these methods shifted tumour biology from a reductionist view toward a systems-level understanding of cancer as an organised ecosystem.

Why bulk analysis is no longer sufficient

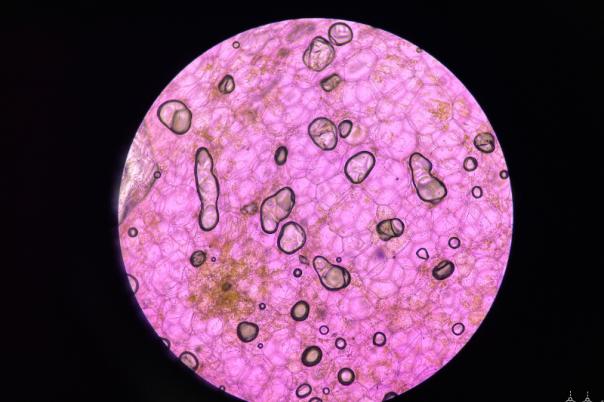

Professor Keller emphasised that traditional bulk sequencing methods, while valuable, obscure critical biological detail. Bulk analysis averages gene expression across all cells in a sample, masking rare or functionally important populations that may drive disease progression or therapeutic resistance.

Single-cell RNA sequencing addresses this limitation by resolving cellular diversity, identifying discrete cell states, and revealing clonal variation. Spatial transcriptomics builds on this foundation by restoring context—showing where cells are located, how they are organised, and how proximity influences behaviour. Rather than answering only “what cells are present,” these approaches allow researchers to ask “where are they, and how do they interact?”

Importantly, Professor Keller framed single-cell and spatial methods as complementary rather than competitive. Single-cell approaches offer depth and molecular resolution, while spatial technologies provide architectural and interactional insight. Used together, they enable a far more complete representation of tumour biology.

Navigating the spatial technology landscape

The rapid expansion of spatial profiling platforms has created both opportunity and complexity. According to Professor Keller, selecting the right technology depends fundamentally on the research or clinical question being asked. Discovery-focused studies may prioritise high-plex, unbiased approaches, while translational or clinical applications may require faster turnaround, higher reproducibility, and simplified workflows.

Current spatial methodologies broadly fall into two categories: RNA-focused approaches that measure transcriptomic activity within intact tissue, and protein-based multiplex imaging platforms that characterise cellular phenotypes and signalling states. Emerging innovations are pushing beyond these boundaries, including spatial epigenomics, DNA-level profiling, three-dimensional tissue analysis, and combined RNA-protein assays on a single tissue section.

No single platform addresses all needs, reinforcing the importance of thoughtful experimental design and complementary approaches.

Reproducibility and integration: shared challenges

As data richness increases, so do challenges around reproducibility and integration. Professor Keller highlighted that reproducibility is both procedural and computational. Rigorous experimental design, standardised protocols, biological replicates, and quality control are as essential as validated computational pipelines, batch correction, and transparent data sharing.

Integrating spatial data with single-cell and other omics presents additional complexity. Spatial assays often sample only a small fraction of a tumour, raising questions about representativeness. Differences in resolution across platforms, batch effects, and the alignment of molecular data across adjacent tissue sections further complicate analysis. Addressing these challenges requires not only algorithmic innovation but also careful biological interpretation to avoid overfitting and misleading conclusions.

Translational momentum in oncology

Despite these challenges, Professor Keller described the field as being in an early but rapidly accelerating translational phase. The most immediate impact has been seen in immuno-oncology, where spatial and single-cell approaches have transformed understanding of immune exclusion, therapy-resistant niches, and cell-to-cell interactions that influence response to immunotherapy.

Biomarker discovery is increasingly shifting away from single genes toward spatially informed cellular ecosystems, incorporating proximity metrics, neighbourhood composition, and interaction networks. While broad clinical adoption will require further standardisation, cost reduction, and faster turnaround times, early applications are likely to focus on high-risk and refractory cancers, where clinical need is greatest.

Panel perspectives: redefining tumour heterogeneity

Building on Professor Keller’s remarks, the panel discussion explored how these technologies are reshaping real-world research and clinical practice.

Professor Simpa Salami, Associate Professor of Urology and Associate Director of the Rogel Cancer Center, described cancer as an ecosystem in which tumour, immune, and stromal cells interact differently across regions of the same tumour. Spatial technologies enable clinicians and researchers to map these interactions, improving risk stratification and informing combination treatment strategies.

Professor Veera Baladandayuthapani, Chair of Biostatistics at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, offered a quantitative perspective. Bulk sequencing captures differences between tumours, while single-cell approaches reveal heterogeneity within tumours. Spatial analysis adds a further dimension by quantifying neighbourhoods, spatial organisation, and interaction strength—critical features when studying the microenvironment.

Dr. Egon Ranghini, Senior Science and Technology Advisor at 10x Genomics, characterised the shift as a fundamental transformation in cancer research. Tumours are inherently heterogeneous, and single-cell and spatial technologies finally align analytical tools with biological reality. However, scalability remains a key challenge, requiring advances in computation, automation, and AI-driven analysis.

From high-resolution data to clinical decision-making

Translating high-resolution tissue data into clinical practice was a central theme of the panel. Dr. Carlo Bifulco, Chief Medical Officer at Providence Genomics, emphasised the importance of practicality. Targeted, lower-plex spatial assays that integrate smoothly with pathology workflows may reach clinical use sooner than highly complex multiplex platforms.

From a clinical perspective, Professor Salami highlighted the broad spectrum of potential applications: tumour classification, prognostic risk stratification, prediction of therapy response, and identification of resistance mechanisms. He shared an example from kidney cancer research where single-cell analysis revealed distinct angiogenic and immunogenic tumour populations within the same lesion, supporting rational combination therapy approaches.

Computation, AI, and the future of spatial biology

The panel agreed that integration of multi-omic and imaging data depends on robust quality control, scalable infrastructure, and interpretable analytical models. Professor Baladandayuthapani stressed that biological context and hypothesis-driven modelling remain essential, even as AI accelerates segmentation, pattern recognition, and visualisation.

Dr. Bifulco and Dr. Ranghini highlighted the growing role of foundation AI models and the importance of pathologist involvement to provide biological and clinical grounding. Early consideration of experimental design, including integration goals and data modalities, was identified as critical to downstream success.

Looking ahead, panellists envisioned biomarker-informed clinical trials, multimodal AI integrating radiology, pathology, and spatial biology, and clearer definitions of spatial biomarkers that can be validated across cohorts and linked to clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

Single-cell and spatial technologies are transforming the tumour microenvironment from an abstract concept into a measurable, interpretable, and clinically actionable system. While challenges remain in standardisation, integration, and scale, momentum across academia, industry, and clinical research is accelerating. Through interdisciplinary collaboration and thoughtful application, spatial biology is poised to play a central role in the future of personalised oncology—turning cellular context into clinical insight.

Explore all Thought Leadership sessions here - https://precisionmedicine.lifesciencexchange.com/thought-leadership/